Bass Magazine Lockdown Check-In With Carlitos Del Puerto

CHRIS JISI · UPDATED: AUG 7, 2020 · ORIGINAL: MAY 17, 2020

We’re checking in with bass players all over the globe to see how they’re staying busy and hanging in during the current lockdown

As the world continues to recover from the Coronavirus, we’re all finding ourselves in unfamiliar territory given the subsequent lockdown that is keeping us off of stages and confined to our homes. Luckily, there’s comfort in the fact that we’re all in this together, and that there are still many outlets for us musicians to keep us active and sane throughout this quarantine. We’re checking in with bass players from all over the world to see what they’re doing to stay entertained, healthy, productive, and safe during this trying time.

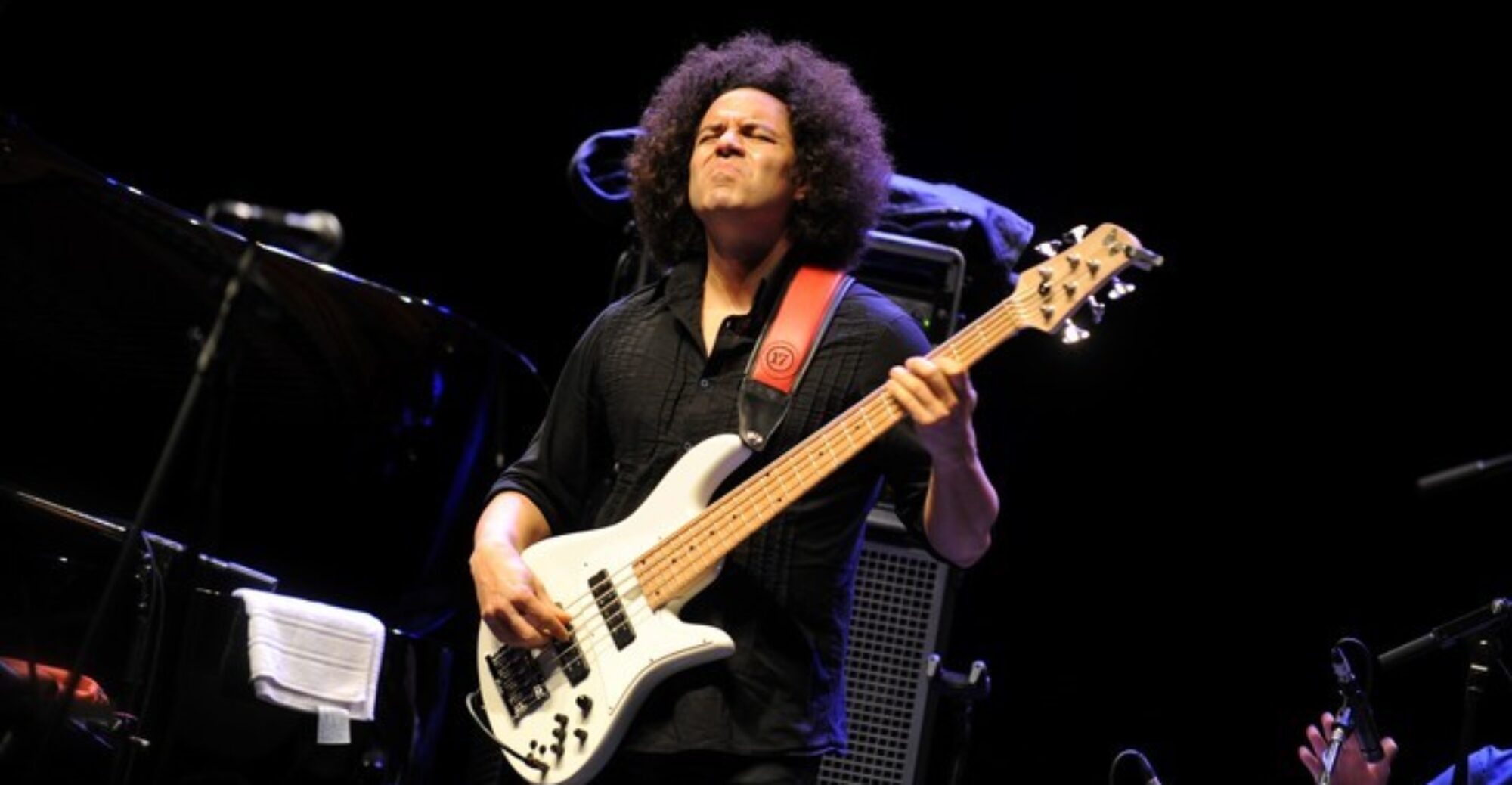

Carlitos Del Puerto – Bruce Springsteen, Steve Lukather, Quincy Jones, Barbra Streisand,

Chick Corea

Los Angeles, California

I’ve been at home and loving it because of how much I travel. With the grace of God, I’ve stayed busy working. I’ve done four albums, one of which I’m especially fond of is by the Latin pop star Juanes. I’ve been doing tracks and videos for Chick Corea, both with the Spanish Heart Band and with Chick, Vinnie Colaiuta, and Bela Fleck. And I’ve been doing a bunch of my own videos on instagram.

There’s always something to practice on the acoustic and electric bass; it’s an endless quest. But I had some accounts to settle with the piano. I’ve been working on my keyboard playing. The piano is such a great instrument; all of music is right there in front of you. It helps my ear and it helps me conceptually, which makes me a much better bass player.

Thankfully, I’ve been busy working at home, so I haven’t had a chance to listen much new or old music, but I plan to. My main source of comfort is my family: My wife Pernilla, who is my rock, my best friend, and my biggest supporter; my mom, dad, and sister, and all of my dear friends. And Freya, my Bluenose Pitbull! She’s so loving, and just looking at her comforts and relaxes me.

I’m happy to say the bass quest is over for me. My Fodera Emperors play and sound great in any musical situation, and they feel like home. My new Italian upright bass is ridiculous! It was handmade in Italy by a young master named Cosimo Fischetti. My old friends at Gallien-Krueger make the best amps for me. I use Fodera and Thomastik strings, Mogami cables, Nylander straps, and I’ve been using Zoom recording products for all of my video postings.

I love history—books, movies, documentaries; I find it fascinating to learn from others who have come before me. I get lost in reading or watching anything historical. I also love running, but I’m limited to safe runs in my neighborhood right now.

I had a whole summer full of tours and projects, which are on hold. I’m looking forward to whatever the future brings. I’m ready to have some fun making music with others. Good things will come, I’m not worried at all.

Stay positive, concentrate on yourself, and keep your spirit strong. I know that may be difficult to do in these times, but it will ensure that when all of this passes you will be ready to work, create, and be productive. The only thing we can control is ourselves, and in doing that we will continue to grow and do well for our families, our communites, and our art.

Read all 180+ Bass Magazine Check-in Features: Here

All check-ins compiled and edited by Jon D’Auria & Chris Jisi

Bass Player Magazine

Carlitos Del Puerto: Rhythm and Blues

CHRIS JISI · MAR 8, 2018

Although equally revered, the working bass hero is different from the bass hero. The bass hero, by virtue of a blinding innovation, band-leading presence, or coveted role in an arena-circuit supergroup seems to exist on a different plane than we mortal bassists. But every thumper can relate to the working bass hero. Sure, they’ve elevated their jack-of-all-genres skills and versatility to transcendent levels, but they’re still filling the role most of us fill. Enter Carlitos Del Puerto, the Los Angeles-based doubler for whom downtime is a forgotten word.

Over the past several years, Del Puerto’s phone has been perpetually abuzz, as music’s elite from across the style spectrum call for his deep, thoughtful grooves, enthusiastic and engaging personality, and the subtle salsa sizzle he brings to his pocket creations. A sampling of his credits include Bruce Springsteen, Quincy Jones, Barbra Streisand, Herbie Hancock, Stevie Wonder, David Foster, John Williams, Chris Botti, Sting, Christina Aguilera, Jennifer Lopez, Clint Holmes, Sergio Mendes with the Black Eyed Peas, Gloria Estefan, Kamasi Washington, the Oscars, Emmys, and Grammys, film soundtracks, jingles, and gaming scores.

Perhaps most eye-opening has been his five-year role with Chick Corea, culminating in Corea and drummer Steve Gadd’s superb collaboration Chinese Butterfly, which also features guitarist Lionel Louke, saxophonist Steve Wilson, and percussionist Luisito Quintero. On the two-disc set, Carlitos crafts rhythmically robust acoustic bass and Fodera 5-string lines that tap into heady harmonies and polyrhythms while also hitting you square in the gut.

At first glance, Carlos Del Puerto Jr.—“Carlitos”—seems destined to have played bass, but the twisty path he took to the top is rife with life lessons and musical awakenings. Del Puerto was born on May 21, 1975, in the culturally rich town of Cayo Hueso in Havana, Cuba. His father is Carlos del Puerto, a Cuban bass god, one of the country’s pioneering electric bassists and electric bass educators, and a co-founder and two-decade member of the legendary Cuban jazz band Irakere (which also boasted reedman Paquito D’Rivera, trumpeter Arturo Sandoval, and pianist Chucho Valdés). In 1979, when Irakere was leaving for its second trip to the U.S., following Columbia Records’ historic Havana Jam concerts (which featured both Cuban bands and Columbia artists like Weather Report, Billy Joel, Stephen Stills, and the CBS Jazz All-Stars), four-year-old Carlitos became separated from his parents at the airport. After a frantic search, they found him in the airport bar, sitting on the lap of Jaco Pastorius! Carlitos’ first instrument was cello, which he studied from grades one through six (the Cuban school systemCarlitos’ first instrument was cello, which he studied from grades one through six (the Cuban school system had Russian instructors, teaching European classical music). At age 14, he switched to acoustic bass, “to make my dad proud,” and, with bow in hand, he began a regimen of ten-hour practice days. The first American music he heard was jazz—everything from John Coltrane to the Chick Corea Elektric Band, thanks to records his friends brought to school and what his dad brought back from tours abroad. He relates, “I had an interest in playing the electric bass, but my dad insisted that I focus only on upright. In retrospect, that was smart because among the younger bassists, I was pretty much the only one who played upright, so I got all of the best gigs.” Del Puerto studied with his dad, took lessons with symphonic bassist Manuel Valdés, and attended the prestigious Esquela Nacional de Arte in Habana. By age 16, he was performing and recording with top artists like pianists Emiliano Salvador and Gonzalo Rubalcaba, and Cubanismo, which led to him winning awards, including Best New Jazz Artist at the 1992 International Jazz Festival in Havana. Carlitos sent a video of himself playing to veteran Los Angeles upright bassist John Clayton and USC Chair of Jazz Studies Shelly Berg, and he got a scholarship to the USC School of Music, arriving in 1996. We began our wide-ranging discussion with a focus on his early influences and his big move west.

Growing up in Cuba, who were your main influences on bass?

My dad, first and foremost, of course. From there it was what we could find from the world outside. Someone had a video of the Oscar Peterson Trio, and I got deep into Neils-Henning Ørsted Pedersen and his three-finger plucking technique, which I used for a while. Hearing John Patitucci on both instruments with the Elektric Band was huge. I found a Jamey Aebersold book by Phil Woods bassist Steve Gilmore with melodic, well constructed walking lines, which opened my mind, as did another Aebersold book by Rufus Reid. I was also into Eddie Gomez, Stanley Clarke, Miroslav Vitous, and Jaco.

What’s a lasting memory from your developmental days?

I used to practice at our house in my room upstairs, which had a little step-out area with about a dozen families within earshot. I’d practice all day long, scratching out scales with a bow; even my dad would yell up,

“Man, give me a break!” But not once did these people ever complain, nor did I ever hear a radio or TV turned up to drown me out. In fact, when I’d get sick, some of them would come around and ask my mother, “Why isn’t Carlitos playing today? Is he all right?”

What was the transition to Los Angeles like for you?

It was a total kick on the butt! I arrived here with my upright and a Yamaha TRB-6, and I was pretty cocky. That is until I started seeing the incredible players around town, like Jimmy Johnson, Abraham Laboriel, Nathan East, Neil Stubenhaus, Jimmy Haslip, and Jimmy Earl, who was a big help in getting my sound together on electric bass. I quickly realized I had to start over. In Cuba, I came from a soloist mentality, and I thought having chops would enable me to cover all the bases. Wrong! I was missing what these L.A. players had: a crazy pocket and an amazing sound. At that point, the only American music I knew was jazz; I wasn’t exposed much to rock and R&B. So I plunged in deep and went back to the roots. I got some Fender-style basses, and I was lucky to find a book that changed my life, Standing in the Shadows of Motown [Hal Leonard, 1989]. From James Jamerson, I discovered Anthony Jackson, which was another revelation. For slapping, I got into LouisJohnson. The groove awakening happened on the upright side, as well, as I dug into heavy pocket players like Ray Brown, Paul Chambers, Ron Carter, and Sam Jones, who is an undersung giant.

How long did it take you to crack the scene?

A long time, but I had a lot to get together. I went from $75-gig to gig for a good eight years, and just when I was at my breaking point, in 2004, I got a call from my friend [keyboardist] Steve Weingart, asking if I wanted to do a rock tour. It was for Steve Lukather—I had no idea who he was, but I learned some valuable lessons. It was a quartet tour, and Luke asked us to meet him at a Mexican restaurant. We sat in a booth and Luke ordered a bottle of Tequila, so we’re drinking and bonding. Finally I asked, “When is the audition?” And he said, “This was it. I know you can play—I just wanted to see if you can hang.” Later, we’re at rehearsals, and coming from the jazz world, I’m standing still and looking down at my fingerboard, thinking about the changes while playing. Luke stops the band and comes over to me and says, “Hey man, you’re sounding great, but can you have some fun? Move around, smile, scream, enjoy yourself!” I did that, and everything changed. People started noticing me: Hey, Carlitos looks like he’s having fun when he’s playing!

What happened from there?

After a few years with Luke, I met Max Weinberg at a rehearsal at the Los Angeles Musician’s Union, and I started doing his big band. That led to about a dozen dates with Bruce Springsteen, starting at the Stone Pony. Then I started working with Chris Botti in his band, which had [pianist] Billy Childs, [drummer] Billy Kilson, [guitarist] Mark Whitfield, and [vocalist] Lisa Fischer. From there, L.A. started opening up for me. Producer/drummer Gregg Field hired me for everything from sessions for Concord to gigs with Booker T., Gloria Estefan, and Carole King. That led to working with Quincy Jones. Harvey Mason got me the Dreamgirls film soundtrack. Vinnie Colaiuta started recommending me after we did a Christina Aguilera album. Rickey Minor hired me to do the Emmys and record for Jennifer Lopez. Randy Waldman gave me record dates and brought me onboard with Barbra Streisand. Producers Ezequial “Cheche” Alara and Dan Warner also provided key opportunities and have been huge supporters of mine.

What do you enjoy about being an in-demand studio and live player in so many different styles?

I love how challenging it is. Every music has a basic language, and if you don’t know it, the music isn’t going to sound right. Because I came to L.A. not knowing a lot of styles, I wanted to learn them authentically, and that research taught me the importance of the bass function. It’s also a tremendous privilege to play with so many different artists. And it’s scary! Ask my wife; she sees how nervous I get before going to any gig. But I prefer that—it keeps you on your game. I got a call for a Blizzard Entertainment gaming score that I thought might be simple, and it was just about the most difficult music I’ve ever played. You have to stay humble, because you never know what you might find.

What’s your basic approach to recording a track?

What happens for me is, when I hear a track for the first time, I instantly know what I’m going to play. I can hear a broad idea of what I’m going to do. Of course, it starts with knowing the DNA of the style, and then drawing from your influences to put some of your voice in there. Early in my session career, I learned that when I played a lot of notes or tried to throw in a fancy fill, it sounded out of place. When I stopped trying to show off to the other musicians and I focused on making the song better, my best work came out. I’m also a big believer that the first take is usually the best take, and every successive take has less magic.

Do you think rhythmically or melodically first?

Rhythmically, man—rhythm is king! If you have a good rhythmic sense, you can play a killer part using just one note [pitch]. I hear a lot of bassists playing ghost-notes and dead-notes in between their notes. That’s cool, although sometimes it can sound like they’re marking time to catch the next accent. Instead, I like to find and play a few good notes that fit the pattern of what the drummer is doing. That sounds cleaner and has more of an attitude than hitting every subdivision. If you think about it, you have the drum kit, the guitar picking, the keyboard stabs—it’s all already there; what’s missing are some big, fat bass notes!

How does your Cuban music background affect what you play?

In Cuba, I was mostly playing jazz. I didn’t do that many Cuban music gigs. Where I really learned the greatness of Cuban music was in L.A. When I first got here, based on my name, all I was doing was salsa gigs; if Celia Cruz was coming through town, I’d put a band together. Of course, I have that music inside of me from growing up around it, so I prefer to think of it like having an accent that makes whatever I play a bit different and my own. Also, in Cuban music the bass is what people dance to, so I always try to make people dance with my bass lines.

How about the bass/drums relationship?

My breakthrough bass/drum moment happened in 1998. I was playing a gig with a veteran drummer who would purposely throw me off by displacing the beat. He thought it was funny, and he refused to show me what was happening. So I bought myself a little drum kit and some drum rudiment books just so I could understand what he was doing. Once I did, I traded the drums for a Fender [laughs]. But getting into drums helped me understand rhythmic displacement and other rhythmic concepts, and they became part of my vocabulary.

Let’s discuss doubling and how you view booth instruments.

I love the acoustic bass and the electric bass equally, but they’re different in a thousand ways, starting with the physical aspects of playing them and the position of your right [plucking] arm. I pretty much treat them as separate instruments, and I don’t do a lot of borrowing from one to the other. One concept I share on both is how I play across the strings. When I play low to high, I alternate my index and middle fingers, but when I come back high to low, I don’t rake the strings with my index finger like most upright players do; I continue to alternate. On both instruments I focus on coordination exercises. It’s not about speed on bass—it’s about coordination. Everyone has one hand that’s faster than the other. For me, my left hand is faster, so I’ve always worked on getting my right hand to the same speed. Equally important is getting both hands to the same level of endurance, especially on the upright.

How did you come to play with Chick Corea?

A few people had mentioned me to him, including Billy Childs, but the first guy to recommend me was Stanley Clarke. I was playing a festival in his neighborhood, and he came up afterwards and was very complimentary. I was blown away. We exchanged numbers but didn’t reconnect until two years later, when I found a phone message from him saying Chick was looking for a bass player and that he had given him my name and number. Forty-five minutes later the phone rang, and a month after that I was on my way to New York to join his band, the Vigil. For me, Chick is the Oracle, so getting to play with him has been an honor and a dream come true.

How did Chinese Butterfly come together?

Chick did one of his online lessons with Steve [Gadd], and it went so well they decided to do a project. Steve suggested me because we had done a Bob James piano concerto album in Japan and some tour dates with Bob and David Sanborn, and Chick agreed. We spent ten days in Clearwater, Florida, learning the music and putting it together, and we also cut four tracks for Philip Bailey’s upcoming album. The vibe was, let’s record live as a band, do a lot of stretching, and go with first takes, which most of the tracks are. That made it fun but also very challenging, because Chick’s music is so melodic that it sounds much more simple than it is to play. Plus, most of the material is in tricky keys, so there weren’t open strings to fall back on. We decided on whether I played acoustic or electric based on the attitude of the song.

“A Spanish Song” has a Cuban feel.

That groove is called a bolero-cha. A bolero is a slow ballad in traditional Cuban music, and as the dancers got better and better, they wanted more of an up-tempo section. So a typical romantic song would start as a bolero, and for the chorus or the bridge the band would play a cha-cha, which implied a double-time feel. Chick’s unison lines there are a beast to play, but that’s what makes the music so rewarding—the initial fear and the joy of conquering it. That’s when people can hear the honesty in your playing. I want to make people feel when I play.

Both the title track and “Wake-Up Call” have a dual feeling going on.

That’s where the fun in getting your rhythmic independence together comes in. With “Wake-Up Call,” which an African element that [guitarist] Lionel Louke adds, you can feel it in 6, or in 4, or in a slow 3 [sings examples of each]—and each one gives the music a whole different dimension. Now, instead of just playing notes or every subdivision on the bass, you’re locking into a master rhythm that breathes. A good analogy is harmony: When you have an uptempo tune with a lot of chord changes that moves through different key centers, a good way to navigate it is to find common tones and keep the melody in mind—that will add space and contrast.

How about your musical relationship with Steve Gadd?

It doesn’t get any better than playing with a legend like that. The first time I played with him was as a last minute sub for Bob James and David Sanborn at a jazz festival. Steve was the first person I saw backstage, and he made me feel so welcome and comfortable. And that’s just what it’s like playing with him. What he’s doing on his kit is so deep support-wise that it makes everything you play sound like it belongs; you actually start to think, Damn, I’m bad!, because all of your notes feel perfect. He’s a master, but he’s also humble and open. At soundchecks I’d play something he had never heard, and he’d ask me about it and we’d come up with grooves.

What advice can you share for those who would like to follow a similar career path?

Assuming you have your playing languages together, make sure you have a good work ethic and a good attitude. That’s as important as your playing. Let people know you appreciate being there, and make everyone feel comfortable and respected. When I get on a gig or session, I truly love being there, and that happiness and positivity is infectious. Be humble and have an open mind; people give me suggestions, and I’m like, Yeah, man—let’s try it. Having both your musical and social skills together will help assure that when a bigopportunity arises, you’ll be able to knock it out of the park.

Rhythm DNA

“Rhythm changed my life!” So says Carlitos Del Puerto, who has developed an exercise he calls Rhythm DNA. “It’s a tool that helps you gain rhythmic independence and coordination, and enables you to have the ultimate control of your time and feel.”

The exercise consists of three elements:

(1) Set your metronome or click on two and four (to emphasize the backbeat feel of a groove), starting at 50 bpm.

(2) Tap the rhumba clave with your foot—not related to playing Afro-Cuban music, but because it’s the one of the most syncopated and challenging rhythmic figures to keep against a straight beat.

(3) Play all eight subdivisions of the quarter-note on one and three, using the notes of a major scale.

Example 1 shows Del Puerto’s recommended starting point. Without your bass, clap on two and four, while tapping the rhumba clave with your foot.

Example 2 contains the main exercise, using the E major scale.

Remember to go slowly, as this is quite difficult, especially if you’ve never worked on your rhythmic independence before. Carlitos advises continuing through the rest of the major scales before increasing the tempo. You can also run them descending, and pick different scales. One additional variation, as you start to get acclimated, is to play different subdivisions within a measure (for example, eighth-notes on one and sextuplets on three). Explains Del Puerto, “This will empower you to feel the music in many different ways,whether you’re playing a straight or a swung groove. It frees your mind rhythmically and gives you more vocabulary to draw from. As a result, you’ll be open to whatever anyone else in the band is doing—like when the drummer plays polyrhythms against the beat—and you’ll be able to introduce your own rhythmically creative ideas. It also sharpens your sense of time, because you’re more familiar and comfortable with all of the subdivisions of the beat.”

LISTEN

Chick Corea & Steve Gadd, Chinese Butterfly [2017, Concord];

Barbra Streisand, The Music … the Mem’ries … the Magic! [2016, Columbia];

Billy Childs, Map to the Treasure:

Reimagining Laura Nyro [2014, Masterworks];

Arturo Sandoval, Dear Diz [2012, Concord];

Steve Lukather, All’s Well That Ends Well [2010, Mascot];

Francisco Cespedes & Gonzalo Rubalcaba, Con el Permiso de Bola [2006, Warner Music Latina];

¡Cubanismo! [1996, Hannibal]

Equipment

Basses: Fodera Emporer 5-string; . French acoustic bass, circa 1820, with Gage Realist Copperhead pickup,

Pirastro Evah Pirazzi strings, and French-style bow; early-’60s Ampeg Baby Bass; ’72 Fender Jazz Bass; ’78 Fender Precision; Lemur Liberty Belle Travel Bass

Strings : Fodera Nickel Roundwounds (.045, .065, .080, .100, .130)

Rig: Gallien-Krueger Fusion 550, 1001 RB, and 2001 RB heads, GK Neo 410 and 412 cabinets, GK Plex Preamp

Effects: Zoom AC-2 Acoustic Creator, B3n Multi-Effects, MS-60B Multi-Stomp; TC Electronic Mojomojo Overdrive, Flashback Delay, Vortex Flanger; T-Rex Bass Juice Distortion

Other: Reunion Blues cases, Nylander straps, Mogami cables, REDDI DI, Radial DIs, Lehle RMI Basswitch

Radial artist Carlitos Del Puerto warms up for tour with Chick Corea

It’s that time of year (at least for the team at Radial which is located in Western Canada) where we buckle down to endure the cold that winter always assuredly brings. What better time to touch base with the ultra-talented, Cuban born bassist Carlitos Del Puerto whose career is as hot as his native country’s habanero pepper on the Scoville scale. We’re warming up already!

It seems the warmth of Cuba followed Del Puerto to the States. He moved to Los Angeles in 1996: „I was a little bit known due to my father (renowned Cuban bass player Carlos Del Puerto) and also because I recorded a few albums in Cuba that were very popular here in the US. ‘Cubanismo’ was one of them, but this was only in the Latin scene. Afterward I branched out to other styles – the city I was in was especially good for what I wanted to do.” Del Puerto quickly grew a resume that included playing with Springsteen, Sting, Quincy Jones and, his idol Chick Corea. „I basically started my career learning his music, but to have the chance to actually play with him goes beyond my wildest dreams.”

Those dreams that began in his youth were well supported: „Growing up in Cuba was a blessing. Cuba is a country with a very rich culture, painters, sculptors, writers and especially musicians. There is music and great musicians everywhere. I had the great fortune to be born into a very artistic household. My mother Maria Llera was a dancer/producer in many shows in Havana and my father, Carlos Del Puerto, was the bass player for Irakere, and also responsible for the modern way of Cuban bass playing.”

Del Puerto is also, of course, grateful for his steady career: „Well, thank God I keep busy. I never take it for granted. I just finished Billy Childs’ record for Sony Masterworks. The music of Laura Nyro, produced by Larry Klein features lots of singers, Renee Fleming, Chaka Khan, Fiona Apple, Esperanza Spalding, Lisa Fischer, Alison Krauss and a few more.”

Some of Del Puerto’s latest work can also be heard on the small and large screens. This includes a national commercial campaign for Honda, featuring vocalist Michael Bolton. The current ad in cycle features the singer rocking it in the snow crooning „It’s a winter wonderland, the snow’s gonna blow, blow, blow.” Del Puerto’s other recent project heads us right back to the sun (whew!): „I also worked on the soundtrack of the film Last Vegas. It was a blast, lots of fun. I was invited by my dear friend Scott Healy, great pianist, to work with him and composer Mark Mothersbaugh on the tracks. It was recorded live, just organ, drums and bass, the old school way. Loved it…..nothing like playing with other musicians and getting that beautiful energy live in the studio. Even more fun is when you go to the movies and hear your work on a great sound system and finally getting to see the movie and enjoy the whole experience… FUN.”

Del Puerto is currently in New York working with Max Weinberg’s Big Band and then heads out on the road for a six month tour with Chick Corea and his new band The Vigil. Del Puerto says he is road ready as he packs along his Radial PZ-DI. „I have been using the PZ-DI on the road with Chick Corea, and also with David Sanborn, and Bob James. Hands down the PZ-DI is the best DI I have ever used on my instruments, it does not affect my sound in any way, it complements it. It gives me all the headroom and clarity that I need, yet is compact and portable, a breeze to travel with. The main feature on the PZ-DI that I love is the switchable input impedance: I can switch between 220k, 1meg and 10 meg-ohms. This is really important to me because it lets me optimize my electric bass and especially my double bass to get the full spectrum of the sound. It has amazing lows, defined mids, and beautiful highs – giving me a full command over my sound. – also it has a low cut filter that comes in super handy when playing in boomy rooms… I LOVE IT.”

Del Puerto will tour with Chick Corea and The Vigil extensively from April through October 2014. The tour stops in some cold spots but it’s certain Del Puerto will heat up every stage he plays.